The railways changed Great Britain profoundly. In the early 19th century, Britain had only a fledgling railway system with just a few dozen miles of track. But within decades, railway mania swept the nation. A vast network of train lines connected all corners of Great Britain, from rural villages to major cities.

This blog post will explore the history and evolution of railways in Britain. We’ll learn about the pioneers who built the first lines, the expansion of the network in Victorian times, the creation of grand stations and key routes, the transition to standardization and more. Railways brought massive economic and social changes, revolutionizing transportation, industry, and everyday life. By the early 20th century, the railways were at the heart of British society.

The First Railways

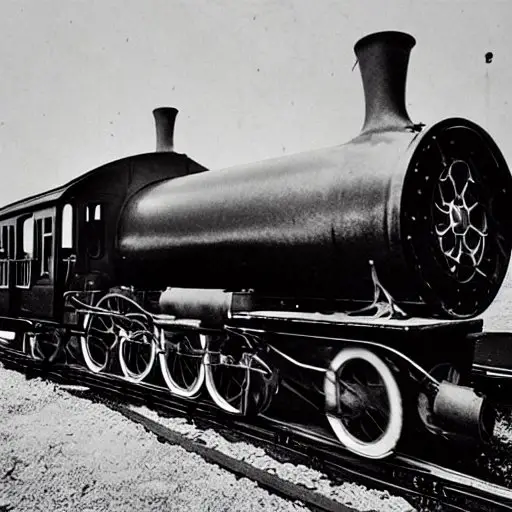

Britain’s first true railway was the Stockton and Darlington in northern England, which began operating in 1825. Using horse-drawn wagons and steam locomotives, it proved goods and minerals could be transported more efficiently over rail than canal or road.

But it was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830, which demonstrated the power of steam railways for transporting people and goods at unprecedented speed. Engineered by George Stephenson, the L&M line used cable haulage through tunnels but locomotives like Stephenson’s Rocket for most of the route.

The success of the L&M generated railway mania in Britain. Dozens of railway companies were formed, each competing to generate passenger and freight traffic by building new lines. Soon major cities like London, Birmingham, and Bristol were connected by an expanding rail network.

Key Lines and the Victorian Railway Boom

Some of the most famous early railway lines in Britain included:

- Great Western Railway – Connected London to Bristol and the West Country. Engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

- London and Birmingham – Linked the capital to England’s industrial heartland in 1838.

- East Coast Main Line – Connected London to York and Edinburgh through eastern England.

- West Coast Main Line – Connected London to Liverpool, Manchester and Scotland through the Midlands and northwest.

- Great Northern Line – Linked London to Yorkshire and Northeast England when completed in 1850.

By 1850, Britain had over 6,000 miles of railway. The network continued expanding rapidly as Victorian Britain experienced massive population and economic growth. By 1900, there were 18,000 miles of track, with railways extending to most towns and villages.

The “Railway Mania” of the 1840’s saw huge amounts of speculative investment poured into railway companies, though many projects failed. Leading engineers like Brunel, Stephenson and Joseph Locke overcame immense technical challenges to build lines through mountains, over rivers and under city streets.

Railway Stations – Temples of Steam

Railways stations grew from simple wooden sheds in the 1830’s to become grand temples of iron, glass and neoclassical architecture as they swelled with passengers. Stations like London’s Paddington, St Pancras, Euston and King’s Cross were built on a giant scale, reflecting the importance of railways to British society.

Great amplifications were needed to handle explosive traffic growth. London’s Waterloo station opened in 1848 with just 10 platforms but was expanded to 24 by the early 20th century.

Stations provided all the facilities busy Victorian travelers needed, from ticket offices to cafes, hotels and shopping arcades. They became bustling small cities, employing thousands of porters, clerks, and station masters.

Standardization and Regulation

By the 1860’s, it was clear Britain’s chaotic, unregulated railway system needed reform. A major Railway Regulation Act was passed in 1868 to set common operating standards. Railroad companies were incentivized to share tracks instead of wastefully duplicating lines. Railway clearing houses standardized ticketing between companies.

Signaling systems were made uniform across regions. Companies began using common station designs, locomotives, carriages and freight wagons that could be shared on the network.

In the 1870s-80s, many private railway companies were consolidated into just a handful of larger regional operators. By 1900, half of route mileage was owned by just four companies. This centralization improved coordination and efficiency.

The Social Impact of Railways in Victorian Britain

Railways turbocharged the Victorian economy, transporting raw materials like coal and agricultural products to power rapid industrialization. They opened new export markets for British goods and enabled cities to grow as workers could commute longer distances.

But railways also transformed everyday life. Suddenly, British people could easily visit relatives or seaside towns for day trips and vacations. Perishable foods like milk, fruit and vegetables could be transported fresh to cities. Newspapers and mail orders were delivered overnight by train.

Of course, rail travel was still too expensive for many working-class Victorians. But railways played a key role in breaking down class barriers and connecting the nation as never before.

Conclusion

In just several decades, Britain was utterly transformed from a country with only a few tentative railway lines to one with an advanced, interlinking railway network at the heart of its economy and society. The railway mania fueled engineering ingenuity, speculative investment bubbles, rapid industrial growth and mass mobility.

The railways fundamentally reshaped the British landscape, economy and the everyday lives of its people. By the early 20th century, railways were a beloved part of British culture and national identity. The legacy of icons like grand stations, steam locomotives and railway posters endure today. Rail continues to provide the vital transportation backbone of Britain.

Jonathan is an Englishman who has travelled via railways in all over Great Britain as well as in other countries worldwide. Despite his enjoyment of travelling around his home island via rail, he wishes that the railway services of Great Britain were up to standard with other countries he has visited.